But beyond that, I think the attraction of living in a Post-Apocalyptic society is pretty basic: there are no rules. There are times throughout the day for all of us when we’d rather be doing something important, something truer, than whatever it is we’re doing to busy ourselves. The “Post-Apocalypse,†as it’s more or less currently envisioned, is a scenario is that requires a sense of enterprise, acuity, and engagement that this modern world simply doesn’t ask of us. There are parts of us all that would probably much rather be fishing for food than making copies; chopping wood instead of paying parking tickets; hunting instead of commuting. It’s easy to see this urge in the fiction we generate because there is so much of it, from Mary Shelley to Guillermo Del Toro. This is nothing new. We know we know this.

When I first began to draft what would become North Dark, it was never consciously conceived of as a “Post-Apocalyptic†work. The plan wasn’t to set something in, say, Bulgaria two generations after a zombie/robot/vampire empire takes hold. Rather, I just wanted to write something where I wouldn’t be aided (at least not very much) by Google or Wikipedia. The landscape, social systems, language—essentially all “the rulesâ€â€” had to be more or less self-generated, or born of the influences that helped engender this book. And this led me further into the genre of Post-Apocalyptic fiction.

A big appeal of this genre for the writer, I believe, is that it reorients the nature of the research. Of course there are books and histories you can read about vanished civilizations, but there aren’t many nonfiction books about our vanished civilization. This requires more speculation and imaginative exploration to arrive at a real depth of knowledge about the world you’re creating so that it seems persuasive rather than derivative. I love listening to artists talk about their creative process to achieve this. Something I hear quite a bit is the ratio of what’s imagined versus what actually makes it to the page. A great example of this comes from the Star Wars prequels (I know, I know). A college roommate and I were watching some mini-documentary on George Lucas and the creative process that eventually generated Episode I, II and III. There’s a moment where all the character designers are having a discussion about how to best craft the moving image of Yoda during a certain moment and they all find themselves debating what the color his tongue and inner mouth would be, and ultimately they have to consult George Lucas on the color of Yoda’s blood. And Lucas knows the answer! (I think it was green but I don’t remember exactly.) The point is that you’ll probably never see Yoda’s blood in a Star Wars film, however, that information exists, it is known, and it impacted something about the content of a Star Wars movie. Artists—nearly universally—have to know so much more about the worlds they create than what actually arrives on the page or canvas or stage. And I think you can sense that depth of knowledge in great work.

With North Dark, I didn’t start out knowing all the answers, however, during the writing process I discovered the information about this world and these characters, much of it didn’t make it to the page, but it’s still embedded in the work. (Examples of this include a race of people called Maunders. It’s never explicitly said who they are, but it’s hoped that this is clear from context and other clues throughout, even the name “Maunderâ€, that these are itinerant, nomadic, deeply impoverished tribes roaming the arctic landscape.) That was the creative process I undertook for North Dark. And it was strikingly liberating.

Ultimately, I think this freedom to imagine, envision, and to world-build in the Post-Apocalyptic genre is a big component of what makes it so attractive to writers. It’s probably much the same for readers; we want to experience a freedom outside of the structure of daily life that we know. This freedom comes with dangers and hardships that our character must suffer, be it a population of undead roaming the planet, or—as is the case with North Dark—the savage rigors of a new Iron Age. Either way, the appeal, I would argue, is ultimate and reckless freedom, whether you’re running from predators or running after your prey.

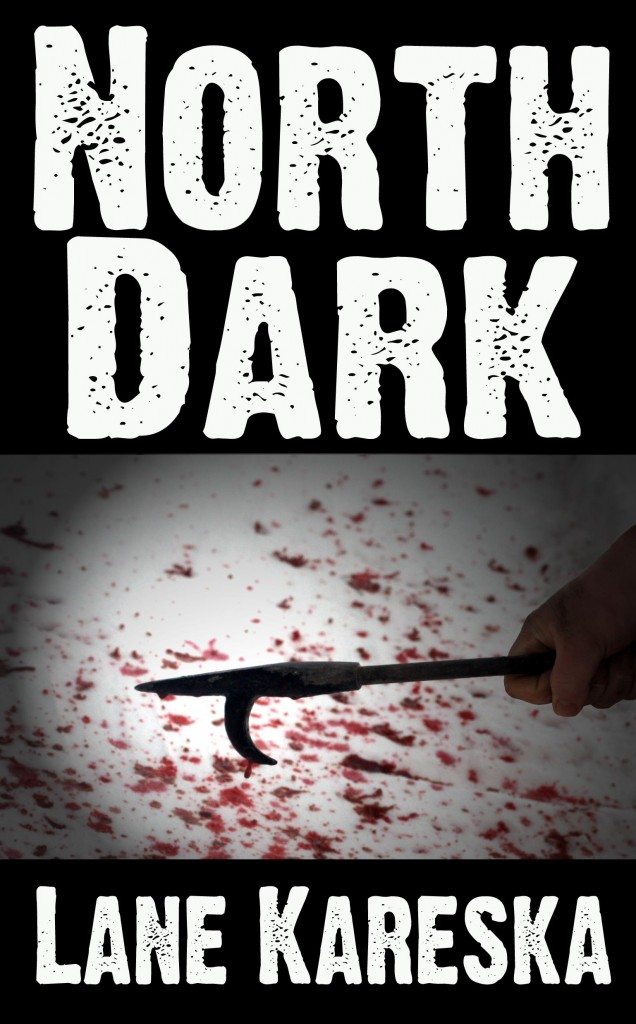

North Dark by Lane Kareska

Synopsis:

Set in a lonesome and barbarous failed state, North Dark is the story of a lone man traveling by dogsled across a frozen wasteland in pursuit of the fugitive who destroyed his family.

Haunted by predators both physical and spectral, the musher’s journey takes him across a deadened tundra, tortured cities and the remains of civilizations long-lapsed into madness. All the while, his enemy slides in and out of striking distance, always one step ahead, always one act of violence away.

Purchase Links:

Amazon: US, UK, Canada, Italy, Germany, Spain, France, Brazil, Japan, India

Â

Author Bio: