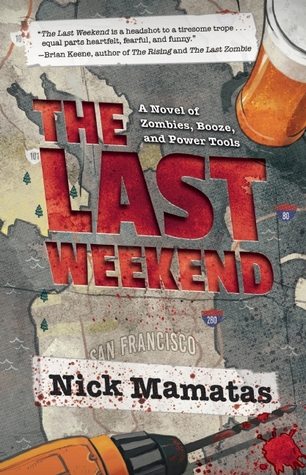

Nick Mamatas

Night Shade Books, an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

Reviewed by William Grabowski

This novel retrieved a sensation comparable to that inspired by my pre-Internet explorations of so-called underground literature: Celine, Henry Miller, Kerouac and the Beats, Bukowski, the spectrum of conspiracy-themed books, pamphlets, videos, and gonzo-style journalism. Nick Mamatas’ The Last Weekend—despite claims from recent reviews—doesn’t read like or otherwise emulate these works, but is filtered through the verve of their question-everything, DIY sensibility.

That feeling soon morphed into delighted fascination, as the authorial camera eye and layered narrative dropped me into the head of Vasilis “Billy†Kostopolos—full-time driller for the City of San Francisco, functional alcoholic, and itinerant scribbler haunted as much by writing as by not writing. A self-proclaimed Rust Belt refugee, bearing witness: “[Y]ou want to hear a zombie story? Fine, I’ll tell you a zombie story.â€

Billy’s occupation is “…essentially a welfare program; something right out of the New Deal.†This obliges him to heed alerts via a network of localband mobile phones and, armed with an off-the-shelf power drill, locate deaders and destroy the brain before they reanimate—a simple job, right? Well, mostly. Mamatas obeys the facts of death and bodily corruption, where after a week of reanimation danger passes, but one might have to block mother’s sickroom door with furniture. She’ll soon smash her hands into jelly, and you’ll just have to sit it out for three days until she falls apart. Drillers provide “Preventative—though slightly posthumous—medicine, after a fashion.†A driller with a folding chair can earn goods and government scrip by setting up in a hospital ER, where doctors, nurses, and patients alike turn away from grotesque post-Outbreak contingency. Too, San Francisco’s hilly terrain challenges the reanimated, as weak bones and necrotized muscles lead to snapped ankles dropping the dead at hill bottoms.

The population tries to go on as before, doing nothing until forced. A menacing movie poster once proclaimed: “Who will survive, and what will be left of them?†Our narrator, Billy, has a good idea: “The social isolates, the outsiders, the third-shifters…[f]orget guns and canned goods. Dog-eared paperbacks of Dostoyevsky, Henry Miller, Colin Wilson…were the best survival tools or at least the best marker of a survivor. Call it anti-social Darwinism.†Billy finds keeping body and soul together a daily trial, and displays a stark-raving sanity. Some of the book’s most horrible moments are also blackly comic, like Billy’s description of how to take care of business in an old man’s bar when a patron, still knocking ’em back, expires . . . and reanimates. Or what to do when a suicide-by-hanging reanimates at home, dangles there purple and growling at her traumatized husband.

Mamatas does not avert his visionary eye, and renders every scene in naturalistic prose. Between drilling gigs, Billy revisits past events in Youngstown, Boston, and elsewhere—boy-girl dalliances and attempts at same, weighted (as they are always) by the ball-and-chain of morality and ethics, burdens temporarily eased through alcohol and other means. Just as everyone has a 9/11 story, the where-were-you-when-the-Outbreak-went-live accounts have become part of collective memory. The rest of the world points at America and laughs.

Billy meets gun-friendly Alexa, who’s recruiting for a raid on City Hall because something useful might be hidden there; might even explain why the City is still relatively safe. After an accidental shooting of a gang member, the two meet Thunder (Billy sizes her up as doable, calculates his chances of nailing her and returning to Alexa). We’re treated to the sort of drinking sessions/philosophical discussions people like me miss having (with or without threats from the animated dead), and Mamatas’ satire flows. Some have detected a Salingeresque air in The Last Weekend. I can see it, but such recognition of incidentals isn’t necessary to appreciate and enjoy the story. It’s full of intelligence, wit, and more-than-canny observations on the foibles of humanity—how we never seem to learn from even our most awful mistakes, and expect life to go on as normal, no matter what. None of this is delivered from the proverbial soap box, but apparent in the characters’ dialogues and action.

Thunder—having seen the wreck of everything around the Bay—wants to know what’s so special about San Francisco. Well, it turns out something indeed is special, and a few theories about that may have been tossed around in scattered meetings. After more adventures, and much drilling on Billy’s and others’ part (including that of a young couple and—never mind, you’ll see), we finally do discover the significance of City Hall, the fate of its elders, and the power of a certain event.

Mamatas is adept at creating menacing scenarios that induce cognitive dissonance, i.e., “Do I laugh here, cringe, or both?†An unusal effect; one I admire. In the literal world, history is driven by economics, greed, war, weather, sex, randomness, and maybe a few well-planned conspiracies. So is the world presented in The Last Weekend. I’d like to think that, in the end, Billy Kostopolos was correct: “Somewhere in Constantinople, a bearded old man is laughing his ass off.â€

Now that strikes me as absurdly as tomorrow’s news probably will.