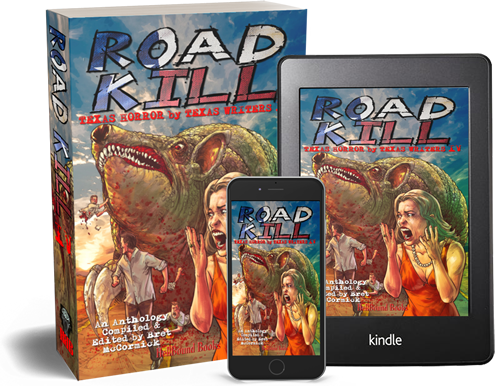

Edited by Bret McCormick

Hellbound Books

Reviewed by Jim Sanderson

As I am wont to do, I read Road Kill: Texas Horror by Texas Writers, Vol 4 for this review while sitting in the corner of a bar by myself. Inevitably, passersby inquired as to what I was doing and, attracted by the cover, asked me about the collection. When I gave them the basic plots for several stories, these emerging horror fans wanted to buy the book from me. This certainly can’t be a bad omen in any discussion of the title’s long-term prospects.

Edited by Fort Worth native Bret McCormick, Road Kill: Texas Horror by Texas Writers, Vol 4, is, as the title states, an anthology of short horror fiction by Texas writers, and they acquit themselves well. In fact, the featured authors so effectively interweave the tales and Lone Star geography that I was often just as intrigued by the chosen Texas settings as I was by harrowing plotlines themselves.

For instance, Corey Lamb’s opening story, “The Girl in the Car†evokes the creepiness of the East Texas nightscape as four young adults drive through the countryside stealing beer from convenience stores. The dialogue is compelling, especially when it begins to don on the narrator that maybe the joy ride is a bad idea. The thieves’ subsequent disruption of a weird ceremonial initiation is like icing on a cake. The authentic East Texas vernacular in Patrick Harrison III’s conversation between a boy and his grandfather regarding a monster that used to emerge “From These Muddy Waters†surprised and captivated me as much as the creature itself. Carmen Gray’s “The Smoke’s Gotta Go Somewhere†depicts a gritty Austin workaday grind from the perspective of a maid trying to navigate immigration crackdowns while taking care of her mother and going to college. And the killer driverless car that kidnaps Andrew Kozma’s protagonist in “The Chauffeur†travels to northeast Houston, giving us a nice feel for the views of downtown and the sights as it passes through distinct Houston neighborhoods.

But to earn the “Road Kill†label, stories must explore the tangible horror in their Texas settings. Edgar Allen Poe, the author who helped create the horror story, explains his theory about “the unity of effect†in “The Importance of the Single Effect in a Prose Tale.â€Â And the collected authors pay homage to their literary ancestor. In order to move us, scare us, spook us, or otherwise have some “effect†on us, Poe argued that a story (any story, not just a horror story) must inspire some big emotional jolt or brace us existentially. And the works in this anthology do. In these stories the Texas characters in their respective Texas locales, delightful in their own rights, bump into numerous horror-inducing effects. Genre readers get their fill of monsters, ghosts, the undead, the subhuman, perversity of all kinds, and murder. And the plotlines and climactic denouncement brim with satisfying wit, satire, irony, social commentary and sometimes just plain fun, even in the face of several strains of darkness.

Some writers start with an effect already having taken place and proceed to logical, earned, but still surprising consequences. These aftereffects are the basis for whole catalogues of popular fiction and film, and several Road Kill contributors envision post-effect plotlines and stay true to them. Apocalyptic events account for two stories of this type. E.R. Bills’ “Nia†offers us a post-nuclear-attack Texas. A newly recruited Marine strolls down a Congress Avenue in Austin that has been reduced to cinder and ash, hunting former subterranean KKK survivalists who resurfaced and took over Texas. And Jeremy Helper’s “The Dark Rift†portrays a small Texas town after an unnamed economic, social, and infrastructural collapse. Helper’s protagonist, an innocent teen girl, gets caught up in the unpleasant and unexpected results of Texas style religion.

A few stories slip a little in terms of consistency and verisimilitude. Rather than staying within the confines of the initial narrative strategy–intimidated by that bully the plot—some writers drift away from the tale they have constructed and lapse into philosophical or editorial comment, which can be disorienting to the reader. Others, however, become literary. William Jensen’s “You Can Outrun the Devil if You Try†has a concise, efficient narrator whose delivery and story lead seamlessly and satisfyingly to the effect. The result is not a “boo†but a more tragic sensibility of fear and pity.

All the stories work well, and I apologize for those contributions that I didn’t mention. Readers of all types should find these tales enjoyable or encounter several that appeal directly to their tastes. We should all look forward to Road Kill V.

Jim Sanderson is the chair of the English and Modern Language Department at Lamar University and is the author of seven acclaimed novels. His works include two award-winning collections of short stories: Semi-Private Rooms, which won the 1992 Kenneth Patton Prize, and Faded Love, which was nominated for Texas Institute of Letters’ 2010 Jesse Jones award for best book written about Texas or by a Texan.Â