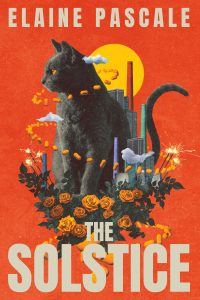

Elaine Pascale

Trepidatio Publishing (April 11, 2025)

Reviewed by Andrew Byers

Elaine Pascale’s The Solstice is a ferocious and uncompromising dystopian horror novel that imagines a near-future America ruled by the old who unhesitatingly prey upon—literally—the young. In Pascale’s chilling vision, society is stratified by color-coded neckbands, with the elder “Red Bands” reigning as decadent, cannibalistic overlords who mark each seasonal solstice with a state-sanctioned purge of the weaker (and younger) classes. Within this nightmarish framework, Pascale weaves a tale that is part socio-political allegory, part psychological horror, and part speculative satire.

The novel opens with a grim trip to the market, as a Lavender-Banded woman—one of the society’s disenfranchised—struggles to purchase desperately needed medication on the eve of the winter Solstice. The Red Bands, once called simply “Boomers,” now rule through opaque policies, nostalgia-fueled cruelty, and an experimental pharmaceutical called Solidox. The Red Bands, you see, now dominate their society ruthlessly, literally preying upon those younger than themselves. The rules of the Solstice are clear: everyone must leave their homes; anyone caught indoors will be executed. The streets become a hunting ground for the Red Bands, who select their prey based on color, class, and whim.

Pascale’s narrative blends visceral horror with sharp social critique. Her dystopia is not built from abstract tyranny but from a warped exaggeration of contemporary generational anxieties and consumerist excess. The Red Bands aren’t merely villains—they are grotesque parodies of entitlement and longevity, dolled up in sequins and boat-themed T-shirts as they disembowel and consume their victims. Pascale leans into the absurdity of their privilege, creating villains who are both terrifying and painfully recognizable.

What makes The Solstice truly disturbing is its plausibility. The world is fully realized and horrifying in its logic. The Solidox drug—developed initially to stimulate appetite in terminal cats—transforms its users into carnivores with enhanced sensory perception and a taste for human flesh. The chapters detailing the drug’s research history and unintended human applications are among the book’s most chilling. Particularly memorable is the backstory of Dr. John, a lonely child prodigy whose desire for maternal approval sets the groundwork for the Red Band regime’s rise.

Despite its bleak premise, Pascale’s novel is deeply human. Through the interwoven lives of characters like Leroy, the store manager trying to survive another Solstice from his supermarket ceiling, or Holly Blue, a woman clinging to normalcy in a collapsing world, Pascale captures the small acts of resistance and survival that persist even in the most brutal conditions. These moments give the novel its emotional weight, even as they underscore the futility of rebellion in a system designed to exploit hope itself.

Pascale’s prose is efficient and evocative, at times almost poetic in its despair. Pascale balances tone and structure with skill, shifting between perspectives and stylistic modes—first-person horror, pseudo-scientific reports, allegorical vignettes—without losing coherence. The result is a novel that is both thematically rich and structurally ambitious.

The Solstice will appeal to fans of dystopian fiction with a taste for the grotesque—readers of Margaret Atwood, Chuck Palahniuk, or Kathe Koja will find much to admire here. Pascale has created a world that is simultaneously surreal and brutally logical, filled with moments of satirical brilliance and gut-punch horror.

This is not escapist fiction; it is a ruthless examination of generational resentment, class cruelty, and the false promises of medical and technological progress. But within that bleak vision lies a dark, compulsive energy—a fierce commitment to storytelling that refuses to flinch.

Pascale’s The Solstice is provocative, original, and deeply unsettling.